Coverage.py

But you don't need to guess. Just grab coverage.py maintained by our guest this week, Ned Batchelder.

Episode Deep Dive

Guest Introduction and Background

Ned Batchelder, a veteran Python developer and core maintainer of coverage.py, has been working on this project for over a decade. He’s an active member of the Boston Python user group and also works at edX focusing on open source software for online education. Ned discovered Python around the year 2000 when exploring Zope and never looked back. Today, he’s passionate about test coverage and measuring how effectively we test our code.

What to Know If You're New to Python

Here are a few essentials that will help you get more out of this conversation:

- Understanding fundamental Python concepts such as

ifstatements, functions, and classes is key. Coverage tools measure which lines and code paths are executed, so familiarity with basic Python flow control is essential. - Having some exposure to Python’s packaging and command-line tools will make it easier to run coverage. You’ll see commands like

coverage runandcoverage report. - If you’ve written a few tests (even simple ones), you’ll be better prepared to appreciate what coverage can do for you.

Key Points and Takeaways

- Line-by-Line Test Coverage Ned highlighted how coverage.py can track which lines of a Python program are actually executed during testing. If code isn’t run, you can’t know whether it truly works. This gives developers concrete data rather than guesswork about “are we testing enough?”

- Tools and links:

- Branch Coverage vs. Statement Coverage While basic coverage tells you which lines of code ran, branch coverage goes deeper by analyzing paths such as

ifconditions andelseclauses. This can reveal missed logic when anifstatement’s false branch never executes, even if there’s no explicitelse.- Tools and links:

- coverage.py docs on branch coverage (general reference)

- Tools and links:

- Configuring Coverage with RC Files Coverage can be configured via a

coverage.rcor.coveragercfile to include or exclude certain files and directories, omit lines based on specific comments or regexes, and tailor reports to your project’s needs. This helps you focus on relevant code and reduce noise.- Notable points:

- Use

[run] source = .to specify your main code folder. - Exclude lines or files you don’t care about (like auto-generated or debug-only segments).

- Use

- Notable points:

- Excluding Files and Lines You Don’t Need Often, test suites or special-purpose code can clutter coverage reports. You can omit those using config or inline comments (e.g.,

# pragma: no cover). But Ned also pointed out that sometimes it’s useful to see test coverage itself for spotting duplicate or lost tests.- Tools and links:

- Measuring Concurrency (Threads and Processes) Python’s concurrency models, like threads,

multiprocessing, and green threads (e.g., gevent), add complexity to coverage. Coverage.py includes specific support for concurrency to track and combine results from parallel or multi-process runs.- Tools and links:

- How Coverage Actually Works (Under the Hood) Coverage.py leverages Python’s built-in

sys.settracefunction, hooking into each line execution. A high-performance C implementation of the trace function speeds this up, so your tests aren’t drastically slowed.- Key detail: It records data in a file for later analysis with

coverage report.

- Key detail: It records data in a file for later analysis with

- Who Tests What (Upcoming Feature) Ned mentioned a future enhancement to coverage.py: identifying which specific tests touch which lines of code. This could enable highly efficient test workflows or help reveal over-tested or under-tested areas.

- Potential benefits:

- Run only the subset of tests that matter after changing certain files.

- Better insights into test duplication.

- Potential benefits:

- sitecustomize.py and .pth Files For capturing subprocess execution, coverage sometimes needs to run before Python actually starts your code. Modifying or adding

sitecustomize.pyor using a.pthfile can inject coverage tracing into new processes automatically.- Useful if your program starts new Python processes that you also want measured.

- Open Source Maintenance and Community Ned encourages developers to engage with coverage.py via GitHub issues, reading the documentation, or even volunteering for open source. He also coordinates with Python’s core devs by testing coverage against new Python releases.

- Additional mention: Boston Python user group is a thriving example of community involvement.

- Testing Philosophy and Value Beyond just coverage, the episode underscored that well-tested code is often better designed code. Code coverage provides an objective measure to see where test gaps might lie, but it also fosters better software architecture and higher confidence in your project.

Interesting Quotes and Stories

"So coverage doesn't know anything about what a test is. It just measures what code got run." -- Ned Batchelder

"There's code inside coverage.py that can't itself be coverage-measured because it's at the heart of how coverage measurement works." -- Ned Batchelder

"Python had no built-in tool that would tell me what I was testing and what I wasn't. So that's why coverage.py really clicked with me." -- (Paraphrased from Ned’s earliest coverage.py experiences)

Key Definitions and Terms

- Coverage: The measure of how much of your code is exercised (run) by your tests.

- Branch Coverage: Tracking all possible paths through your code, such as both the

ifandelsebranches. - Coverage RC: A configuration file (

.coveragerc) that tells coverage.py which files or lines to measure or exclude, among other settings. - Concurrency: Running code across multiple threads or processes, requiring coverage to track each context properly.

sys.settrace: A Python function for intercepting every line of code execution, key to how coverage.py collects data.

Learning Resources

- Python for Absolute Beginners: Perfect if you’re new to Python and want a thorough yet easy-to-follow start.

- Getting started with pytest: Once you understand Python basics, learning to test effectively with pytest can pair excellently with coverage.py.

Overall Takeaway

Test coverage is more than just a percentage score. It’s a powerful tool to visualize, debug, and deepen our understanding of how well our tests actually exercise our applications. Ned Batchelder’s coverage.py has become the go-to tool for Python developers wanting measurable confidence in their code. By using coverage and good testing practices, you’ll not only write more reliable programs but often discover ways to refine and simplify your code’s design.

Links from the show

Ned on the web: nedbatchelder.com

Coverage.py: coverage.readthedocs.io

Mentioned: Python for .NET: pythonnet.github.io

Package: check-manifest: pypi.org/project/check-manifest

Episode #178 deep-dive: talkpython.fm/178

Episode transcripts: talkpython.fm

---== Don't be a stranger ==---

YouTube: youtube.com/@talkpython

Bluesky: @talkpython.fm

Mastodon: @talkpython@fosstodon.org

X.com: @talkpython

Michael on Bluesky: @mkennedy.codes

Michael on Mastodon: @mkennedy@fosstodon.org

Michael on X.com: @mkennedy

Episode Transcript

Collapse transcript

00:00 You know you should be testing your code, right? How do you know whether it's well-tested?

00:03 Are you testing the right things? If you're not using code coverage, chances are you're guessing.

00:08 But you don't need to guess. Just grab coverage.py maintained by our guest this week,

00:12 Ned Batchelder. This is Talk Python To Me, episode 178, recorded September 10th, 2018.

00:18 Welcome to Talk Python To Me, a weekly podcast on Python, the language, the libraries, the ecosystem, and the personalities.

00:38 This is your host, Michael Kennedy. Follow me on Twitter, where I'm @mkennedy.

00:43 Keep up with the show and listen to past episodes at talkpython.fm, and follow the show on Twitter via at Talk Python.

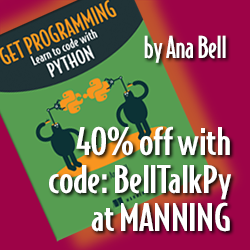

00:49 This episode is brought to you by Brilliant.org and Manning.

00:53 Please check out what they're offering during their segments. It really helps support the show.

00:57 Ned, welcome to Talk Python.

00:59 Hi, thanks, Michael. It's great to be here.

01:01 It's great to finally have you on the show. I cannot believe we are at episode 178,

01:06 and you have not been a guest on the show. How did this happen?

01:08 I know. You're doing something wrong over there. I don't know. You're doing something great over there.

01:12 You've got to episode 178, which is astounding.

01:15 Anyone who says, I'm going to do a thing and then does it 178 times, clearly is doing something right.

01:19 Yeah, we're coming up on, I think on three years.

01:22 Yeah, actually, maybe over three years. So I got to do some quick math.

01:25 But yeah, it's been going for a while, and it's really fun. I'm just absolutely loving it.

01:29 And we're going to dig into a project that you've been actually working on more than three years, right?

01:34 Yes. So coverage.py is a project that I've been maintaining for 14 years, which seems crazy.

01:40 That is really amazing. And kudos to you for doing that. That's great.

01:44 I think what I realized about myself is that I'm very inertial.

01:47 It's hard for me to start new things, and then it's also hard for me to stop old things.

01:51 Once you get them rolling, they just keep going.

01:53 That's right.

01:53 That's right.

01:54 It's not a bad trade at all.

01:56 So before we get into all the details of code coverage and so on, let's just get a little background on you.

02:02 How did you get into programming in Python?

02:03 Well, so I've got kind of an unusual story that way.

02:06 So I'm fairly old for the Python world.

02:10 I'm 56 years old, and I got into programming because my mother was a software person, too.

02:15 She was a programmer in the 1960s and 70s, 80s and 90s, I guess, until she retired.

02:20 Back when programming was really hard.

02:22 There was no internet, not many books.

02:25 Programming was different back then.

02:26 Yeah, there was definitely no internet.

02:28 The books were in a big, huge three-ring binder at the other side of the room, et cetera, et cetera.

02:33 But the cool thing was that she would bring home some of those books.

02:36 So I remember as a kid looking through the IBM 360 programmer's manuals and puzzling over what this stuff might mean.

02:42 So I sort of come by programming naturally.

02:45 I've been doing it for a while.

02:46 I joke that it's the only skill I've got, so it's a good thing that people will hire me to do it.

02:51 And I got into Python probably in the year 2000, maybe 1999.

02:56 I'd been working at Lotus on Lotus Notes, which is a collaboration environment.

03:01 Was that in C++ before?

03:03 Well, Lotus Notes is written in C.

03:05 But the reason, the way I got to Python was that Lotus Notes, with its access controls and collaboration controls, someone said, oh, you should look at this thing called Zope.

03:13 It also does stuff like that.

03:15 And I looked at Zope, and I thought, you know, Zope's kind of cool.

03:17 I don't really need that.

03:18 But this Python thing it's written in seems kind of interesting.

03:21 And so basically from that point on, when I had a choice of tools for writing some little tools or some scripting or some automation, I would reach for Python.

03:29 And that's just grown and grown since then.

03:31 Now, I guess I've been using it for 18 years or so.

03:34 That's really cool.

03:35 And Python itself has grown with you, right?

03:38 I mean, Python of 18 years ago is not Python of 2018.

03:41 Yeah, and it's funny.

03:42 I don't even know what version of Python that was.

03:45 It might have been a 1.x, I guess.

03:47 Yeah, and Python has definitely grown.

03:50 I feel like I sort of made a technology choice there, and it's worked out very well.

03:55 I've watched Python grow into at least two new major niches since then, into web dev and now into data science.

04:02 I feel much more comfortable in web dev.

04:04 I feel a little bit like I'm getting left behind with the data science and machine learning.

04:09 And even just hanging out where people ask questions about things, it's very clear that the center of interest is outside my expertise now.

04:18 So I've got a lot to learn.

04:20 It's interesting that you can be an expert in Python after 18 years and be a beginner at the things that people want to use Python for.

04:27 Yeah, that's super interesting.

04:28 Yeah, like if somebody said, hey, Michael, go do this plot with Matplotlib and get this data loaded up with Pandas.

04:34 I'm pretty sure I could not do that without documentation or examples in front of me because I spend most of my time writing web and database code.

04:41 Yeah, and I have done Matplotlib in a little bit of notebooks.

04:45 And I'm, you know, I am like the typical, I'm on Stack Overflow.

04:48 I'm just searching for stuff.

04:50 I see a chunk of code.

04:51 I don't know what it means.

04:52 I paste it in.

04:52 It seems to work.

04:53 We're done, you know.

04:55 And I would love to have a deeper foundational understanding.

04:58 But I don't have day-to-day problems that need those tools.

05:01 So there's not much chance for me to really get that learning.

05:04 Yeah, I feel like it's sort of bimodal now.

05:08 There's these two big areas that Python is really being used a lot in, at least.

05:13 And, you know, did you catch Jake Vander Plaas' keynote at PyCon 2017 about Python being a mosaic?

05:20 I didn't.

05:21 2017 was the PyCon I missed of the last decade of PyCons.

05:25 That was a good one.

05:27 Well, basically it was, look, there's all these different ways and people are using Python and their goals.

05:32 And their entire purpose of using Python may be very different than the person you're sitting next to.

05:38 But if you learn to appreciate it, it just makes it richer.

05:41 And I thought it was a really great way to sort of say, like, look at all these things people are doing.

05:45 They have different motivations and whatnot.

05:48 But it's just as valid Python in style.

05:51 It's for a different use case.

05:53 Right, exactly.

05:53 Yeah, I feel like we're definitely there.

05:55 Yeah, one of the things that I do is organize the Boston Python user group.

06:00 And we have project nights every month.

06:02 And we just get a big room with a lot of round tables.

06:05 And we put labels on each table.

06:07 So there's a table labeled beginners and a table labeled web.

06:09 And then we get data and we get science and we get hardware.

06:12 And it's just really interesting to see the variety of uses that people are putting Python to.

06:18 And there was a woman who came last month, was sitting at the beginners table.

06:22 And towards the end of the night, I was asking her more about what she wanted to do.

06:25 And she mentioned biology.

06:27 And I said, oh, you should have at the beginning of the night, you should have stood up and said, I'm doing biology.

06:31 We could have found you some biologists to talk to.

06:33 And she laughed like I was joking.

06:35 But then I introduced her to the four or five biologists across the room who were doing biology with Python.

06:41 So it's really a very rich ecosystem of expertise and individual domains, which is fascinating.

06:49 One of the things I love about Python is a lot of people seem to come to it with another expertise, kind of like you were just saying, right?

06:56 Like if you're a C++ developer, there's a good chance you may be a developer first, right?

07:02 But if you're doing Python, you may be something else first that uses Python.

07:05 And I think that just makes us a richer community.

07:08 That's why I think it's doing so well in data science is that it's, for whatever reason, it's the kind of language and environment that those types of people can succeed in.

07:17 Yeah, absolutely.

07:19 So you mentioned the Boston user group.

07:21 This is a global podcast.

07:22 The internet doesn't have a zip code or whatever.

07:25 But for people generally in the Northeast, like you want to just tell them really quickly about it so they can find it if they don't know?

07:31 Sure.

07:31 So the Boston Python user group is a big group.

07:33 We run events twice each month, generally, a project night, which is basically a two and a half hour unstructured hackathon with some sorting by topic, like I just described.

07:43 And then most months we also run a presentation night where we try to find people to give talks.

07:47 We did lightning talks for August.

07:49 I'm working on grooming a web scraping talk for September, and we're going to have science talks for November.

07:56 And we're very friendly.

07:58 We're big and open.

07:59 We're on meetup.com or bostonpython.com.

08:01 And if you're anywhere around, come and see us.

08:04 We've had people travel as long as three hours to get to events.

08:08 So all of New England is kind of in scope.

08:11 Yeah, absolutely.

08:12 Well, I guess it depends on the time as well, right?

08:14 Rush hour and all that.

08:15 Three hours could be not far away in certain parts of Boston.

08:18 That's true.

08:19 The really memorable one was the father and son who took a three-hour bus ride down from Maine.

08:23 And that kid was 13, and he was one of the smartest people I've ever met.

08:27 And they were going to leave and get home at like 2 in the morning based on the bus schedule to have attended.

08:32 They only came once.

08:33 And I mean, I don't blame them, but it was very impressive.

08:36 No, that's cool.

08:36 Is there any way to remotely attend?

08:38 Any streaming options?

08:39 We've never managed to be routine about videoing the presentations, which is really unfortunate.

08:46 Because even in Boston, we have 8,000 people on the meetup group, and we can only fit 120 people in the room.

08:52 And we always have a waiting list.

08:53 So lots of people would like to see video.

08:55 But we have just never managed to find the staff to make it a regular thing.

09:01 It's almost got to be somebody's, their responsibility, their role to just do that, right?

09:05 Absolutely.

09:06 Yep.

09:06 And they've got to show up every time, et cetera, et cetera.

09:09 Yeah.

09:09 So another thing that you do, and I'm also super passionate about, has to do with online education, right?

09:14 Right.

09:15 Yeah, my day job is at edX.

09:17 EdX.org is the website that was founded by Harvard and MIT and puts university-level courses online.

09:23 We've got, I don't know, 2,000, 3,000 courses from 130 different institutions at this point.

09:30 And it's all Python and Django, and it's all open source, which is the thing that really appeals to me because I'm an open source guy.

09:35 I actually work on the open source team here at edX.

09:38 So we are encouraging and enabling other people to use our software to do online education.

09:43 There's about 1,000 other sites besides edX.org that use OpenEdX to do their education, which is thrilling.

09:50 Because as great as Harvard and MIT courses are, there's all sorts of other kinds of education that those institutions will never provide.

09:59 We just recently discovered there was a website in Indonesia which has something like 150 different courses all very, very focused on specific skills that might lift someone out of poverty.

10:11 You know, how to be a maid, how to do hairdressing, how to raise chickens, how to fix small engines, how to catch fish, like just all sorts of things.

10:19 Super practical vocational type things.

10:21 Super practical vocational in Indonesian for Indonesians.

10:25 And edX.org, as many courses as we're going to get.

10:29 We're never going to deliver those courses.

10:30 So having the software be open source, you know, we give away education on edX.org and we give away the software to give away education to the rest of the world.

10:38 And there's 1,000 sites out there that are using it, which is really, really gratifying.

10:43 Oh, that's awesome.

10:44 It sounds like a great project.

10:45 And it's mostly Python and Django?

10:47 Yeah.

10:48 It's almost, I mean, JavaScript, of course, too.

10:50 But yeah, it's all Python and Django.

10:52 And it's almost all open source.

10:54 Very cool.

10:55 And we're hiring, if anyone, you know, tell them Ned sent you.

10:57 There's a referral bonus.

10:58 Do you guys have remote positions or it's got to be in Boston?

11:03 The easiest thing to say is, let's say it's got to be in Boston.

11:06 Yeah.

11:07 We're not super good at remote, which is something I wish we could get better at.

11:11 But that's the reality of the situation today.

11:13 Yeah.

11:13 So if people are listening and they want a cool Python job in the general Boston area or they're willing to get there.

11:19 Yeah.

11:20 Yeah.

11:20 Awesome.

11:20 Get in touch.

11:22 Let's see what we can do.

11:22 Yeah.

11:23 That's really great.

11:24 It sounds super fun.

11:25 Okay.

11:25 So let's talk about this brand new project that you just started called Coverage PY.

11:30 That's right.

11:31 This is a podcast from December of 2004.

11:33 Exactly.

11:34 All right.

11:36 So let's talk about what is code coverage and what is this project?

11:38 Okay.

11:39 Well, and let me just start with one thing, which is I didn't actually start this project.

11:43 This project was started by a guy named Gareth Reese.

11:45 And back in 2004, I was working on a different Python thing and I wanted to use some code coverage on it.

11:53 And I found this thing called Coverage.py and it worked almost exactly the way I wanted.

11:57 And the way it didn't, I tried to make a change and I tried to get it to Gareth and Gareth didn't seem to be reachable.

12:03 So I just sort of published it with my change.

12:05 And 14 years later, I'm the maintainer of Coverage.py.

12:10 That's how open source works, right?

12:12 That's how open source works.

12:14 Yeah.

12:14 I'm mulling the idea of doing a lighting talk called Lies People Believe About Coverage.py, one of which is that I started it.

12:22 Yeah.

12:23 Okay.

12:24 But to answer your question, so what is code coverage?

12:26 So the idea of code coverage is you've got some product code that you've written, meaning the code you actually want to write.

12:33 And then to make sure that that code works, you write some tests.

12:36 And I'll give the entire audience the benefit of the doubt and say you have written tests.

12:41 But now you need to know, are the tests actually doing their job, which is proving that your code works?

12:47 And one way to test your tests essentially is to observe the tests running and see if all of the lines of your product code were executed by the tests.

12:59 Because if there's a line of code that isn't executed when you run your entire test suite, then there's no way that line of code can be tested.

13:06 The converse isn't true.

13:08 If the line of code is run, it still might not be properly tested.

13:11 But if it isn't run, then it's definitely not properly tested.

13:14 Absolutely.

13:15 If it was never executed, you know nothing about it.

13:18 Absolutely.

13:18 That's right.

13:18 There's no way you know how that line of code works.

13:22 So the code coverage in general is the automation of that process, which is it is a tool that can observe a program being run and can tell you what lines of code were run in the program.

13:34 And notice in that sentence, I didn't say anything about tests.

13:36 Coverage doesn't know anything about what a test is.

13:39 It's just that typically the program you want to watch is your code while the tests are being run.

13:44 But you could run coverage for any reason to know what parts were run or not.

13:48 Right.

13:49 This is typically most spoken about in terms of unit testing and other types of tests.

13:53 But one example that comes to mind right away is I've got some app.

13:57 It's been handed down from person to person and somehow it arrives in my lap and they're like, Michael, you've got to now add a feature or maintain this thing.

14:07 And it's a big scrambled mess.

14:09 And the person who knows all about it is gone.

14:11 Maybe I just want to know when it does its job, does it ever even call this function?

14:15 Right.

14:16 Like there could be all sorts of code in there that is just nobody wanted to remove it because they didn't know for sure it was OK.

14:22 But if you can run the coverage and say, actually, no, it's never executed.

14:25 Let's delete it.

14:26 That's right.

14:26 That's right.

14:27 So long as you are sure that you know how to fully exercise.

14:31 Yes.

14:31 Yeah.

14:32 You got it.

14:33 That is another another thing.

14:36 But I've spent hours trying to understand what a particular function does and how it influences like a big program just to realize that actually the reason any changes I'm making to this section or try to make it do a thing have no effect because it's not being called.

14:51 Right.

14:51 Yeah.

14:51 It's super frustrating.

14:53 Right.

14:53 So coverage can be used for that.

14:54 But like you say, the 99.9% use case for any code coverage tool, including coverage.py, is for it to observe your test suite being run and then to tell you about your product code, which lines were run and which lines weren't.

15:07 Right.

15:08 And the idea being that the lines that weren't, that's what you focus in on.

15:12 And you think about how can I write a test to make that line of code be run.

15:15 And you'll gradually increase the coverage.

15:17 And then you're right.

15:18 Or you make a conscious decision.

15:19 This part we don't care to test.

15:21 Right.

15:21 That's right.

15:22 You can also decide that.

15:24 Yes.

15:24 But I think the important thing is, even if you're in that place, there is a core reason your application exists.

15:31 There is a thing that it does and there's stuff that supports it doing that.

15:35 Right.

15:35 If you're writing a stock trading application, the stock decision engine had better have a good bit of coverage on it.

15:41 Yes.

15:42 Or you failed with your test.

15:43 Right.

15:44 Testing the login like crazy doesn't help the core engine do anything better.

15:48 Right.

15:48 You could decide you're going to increase coverage on the parts you care about.

15:53 And coverage doesn't really have any opinions about this.

15:55 It's designed to just tell you something about your code.

15:59 I've found over the years I am drawn to projects that are all about helping developers understand their world better.

16:06 And coverage is one of those ways.

16:09 Right.

16:09 You wrote something and you wrote something to test it and you thought it was testing it.

16:13 And, oh, is it?

16:14 Well, coverage can tell you whether it is.

16:16 Yeah.

16:17 I really love that, the way it works.

16:19 So I guess maybe we could talk a little bit about how you run it.

16:22 Like, is this something you put in continuous integration?

16:24 Is it a command line tool?

16:26 Like, where does it work?

16:27 Right.

16:28 So the simplest thing is it is a command line tool and you can run it in your continuous integration on Travis or something.

16:34 Or you can just run it from the command line.

16:35 The design is that the coverage command has a number of subcommands, one of which is run.

16:40 And when you type coverage run, anything you could put after the word Python, you could put after coverage run.

16:46 So if you used to run your program by saying Python prog.py, then you can say coverage run prog.py.

16:53 And it will run it the same way that Python would have run it, but under observation.

16:56 That will collect a bunch of data.

16:59 And then if you type coverage report, it will give you a report.

17:02 And for every line, every file that got executed, it will tell you things like how many statements there are, how many got executed, how many didn't get executed, and therefore what percentage of them were executed.

17:14 And then a big total at the end.

17:16 Yeah, that's really cool.

17:17 So I could say like coverage-m unit test in some file or something like this?

17:23 Yeah, coverage run-m.

17:25 Yeah, okay, gotcha.

17:26 Right, dash-m unit test.

17:27 Yes, I'll just leave it at that, yes.

17:29 And there's also a pytest plugin, right?

17:32 There are plugins for pytest and for Nose.

17:34 And I'll be perfectly honest with you, I'm not a huge fan of the plugins because it's just another bunch of code between you and me, sort of.

17:44 Like, I don't understand exactly how those plugins work, so it's hard for me to vouch for them doing what you want them to do.

17:52 But yes, there are plugins for pytest.

17:55 So there's pytest-Cov, and when you install it, you now have dash-dash-cov, a few, about half dozen dash-dash-cov options to pytest to say things like, I want you to only look at these modules, or I want you to produce this kind of report at the end.

18:09 So it's much more convenient in that you don't, you can get all of the coverage behavior in one pytest run, rather than having coverage run pytest, and then coverage producing a report as two separate commands.

18:20 But like I said, there's a trade-off there in that if the plugin isn't doing what you want, then it's a little bit trickier.

18:26 Now you've got to figure out, is it the plugin, or is it coverage, or is it my script that's doing it?

18:31 It's one more variable in there.

18:33 Yeah, it just makes it a little more complex.

18:34 Okay, interesting.

18:35 Another place that I really like to run coverage.py is from PyCharm.

18:41 I don't know if you've ever seen the integration there, but that is just incredible.

18:44 You right-click on some part of your code and say, run this with coverage, and then you get a report in PyCharm.

18:50 But PyCharm, the editor itself, actually colors each line based on the coverage, which I think is a really nice touch.

18:56 Yeah, PyCharm is really an amazing IDE, which I don't actually use because I'm old.

19:01 There's also a Vim plugin, I believe, to do similar things to get the coverage data and to display it to you in Vim and probably for Emacs as well.

19:09 Oh, that's cool.

19:10 Yeah, the more convenient we can make it for people to see the information, the better off it's going to be, the tighter feedback loop you've got.

19:17 And right there in the editor is the best place to see it because that's where you're going to have to be dealing with the code anyway.

19:23 You're not trying to correlate some report back to some file.

19:26 You just look at it like, oh, why is that red?

19:28 That should be green.

19:29 What's going on here?

19:29 Right, exactly.

19:30 And coverage will produce HTML reports that are colored red and green and actually have a little bit of interaction if you want to focus in on things.

19:37 But if other IDEs or whatever can produce displays that make it more convenient for people, then more power to them.

19:45 Coverage has an API, Python API, which is, I assume, what PyCharm is built on, although they could be also just doing subprocess launches and things like that.

19:53 So, yeah, I'm happy to have people get access to the power of that coverage measurement, however they're most happy with.

20:01 Yeah, that's really great.

20:03 So, one of the things that I kind of hinted at before with the core trading engine and certainly with, say, like your test code, you probably don't care about looking at the analysis of the coverage of your test code.

20:15 You would like to see the analysis of your code under test.

20:19 So, how do you exclude some bits of code from being analyzed?

20:22 All right.

20:23 So, I'll answer your question first, and then I will challenge the premise of the question.

20:26 Okay.

20:27 Sure.

20:27 Good.

20:29 So, coverage gives – there's a bunch of controls that you can get used with coverage to, say, basically to focus its attention on the code you want.

20:37 If you run coverage just the way I started with, it will tell you about a lot more than what you care about because it's going to tell you about every library you've imported, even if it's not your code.

20:47 And that's partly because that's the way it used to be and partly because it's hard to know what counts as a third-party library versus your code if you're running your code in an installed setting and so on and so forth.

20:59 So, there are controls to focus coverage in on the code you want.

21:05 The simplest is the source option.

21:07 And the source option says, I'm only interested in any source code that you find from this tree downwards.

21:12 And, for instance, source equals dot is often a very good choice.

21:16 choice because it means I'm in the current working directory.

21:19 Here's my code.

21:20 Don't tell me about any code you find anywhere else.

21:22 But even more than that, you can say things like omit these file paths or only include these file paths.

21:30 So, there's a lot of controls there to focus coverage in.

21:34 And that's because an automated tool is great unless you're constantly knowing more than the automated tool tells you.

21:41 Like, if the automated tool is like a noisy kindergartner yammering at you and you have to tell it, keep thinking to yourself, shut up about that.

21:51 I know that's not what I'm concerned about.

21:53 Then the tool is not useful.

21:56 Yeah.

21:59 This portion of Talk Python To Me is brought to you by Brilliant.org.

22:02 Many of you have come to software development and data science through paths that did not include a full-on computer science or mathematic degree.

22:09 Yet, in our technical field, you may find you need to learn exactly these topics.

22:14 You could go back to university.

22:15 But then again, this is the 21st century and we do have the internet.

22:19 Why not take some engaging online courses to quickly get just the skills that you need?

22:24 That's where Brilliant.org comes in.

22:26 They believe that effective learning is active.

22:29 So master the concepts you need by solving fun, challenging problems yourself.

22:33 Get started today.

22:35 Just visit talkpython.fm/brilliant and sign up for free.

22:39 And don't wait either.

22:40 If you decide to upgrade to a paid account for guided courses and more practice exercises,

22:45 the first 200 people that sign up from Talk Python will get an extra 20% off an annual premium subscription.

22:51 That's talkpython.fm/brilliant.

22:55 People will stop using it, right?

22:57 Like if it becomes too noisy and too annoying, then you're like, well, it would have been helpful.

23:00 But it's just so much noise.

23:02 Forget this thing.

23:03 Right.

23:03 Or there's actually useful information in it that they can't see or whatever.

23:08 So it shouldn't be that the way you use coverage is you run it, you get a report, and then you skip over all the stuff you know you don't care about to hopefully see the stuff you do care about.

23:19 So there's a lot of controls and coverage to let you be the smart one in the room and let it be the savant about the one thing that it is smarter than you about, which is what code got run.

23:31 So in addition to being able to exclude or include file paths and modules, you can actually put comments in your code to tell coverage, this line isn't run, but I don't care.

23:43 Like, don't tell me about this line anymore.

23:45 I'm okay with it not being run.

23:47 Yeah.

23:47 One of the examples you gave was the repper method, dunderrepper.

23:50 Right.

23:51 Do you really want to write a test that instantiates an object and just prints it just to get that function?

23:56 Right.

23:57 Like, no.

23:57 And I've got lots of dunderreppers in the coverage.py code, and they're only ever run when I'm debugging coverage.py.

24:03 I'm in a debugger, and I want to see what that is.

24:06 You want to see the string representation better than this type at that address.

24:09 That's right.

24:10 So I write a dunderrepper, and I don't want to be told that it's not being executed in my test suite because I don't run it in my test suite.

24:17 So – and in addition to putting comments on lines, what you can actually do with coverage is there's a coverage.rc file to configure coverage, and you can actually specify a list of regexes, and any line that matches one of those regexes will be excluded from coverage measurement.

24:32 And that's how the comment works.

24:34 The comment is a regex pattern by default in that setting.

24:37 But, for instance, when I run coverage, I put, like, def space dunderrepper as one of the regexes.

24:44 And that will match all my reppers, and then they'll all be excluded from coverage, and I don't need to worry about them anymore.

24:49 Yeah, that makes a lot of sense.

24:50 So you could put the comment hash, pragmical, and no cover, but you might not want that in your code all over the place.

24:58 Right.

24:58 You'd have to remember to put it in and et cetera.

25:01 Yeah.

25:02 People who don't care about it, they're like, why is this in this code?

25:04 Or, you know, they write their code and they don't add it.

25:06 Yeah, it's just – sometimes it's better to have it separate.

25:09 Yeah.

25:09 Right.

25:10 And what I actually have done, because I'm a little obsessive about it in coverage.py itself, is I have a half dozen or ten different comment syntaxes that I'll use to exclude lines from coverage because they're being excluded for different reasons.

25:24 Like a line that only runs on Jython, I will exclude from coverage because I'm not doing coverage measurement under Jython, even though I want to have a little bit of Jython support in the code.

25:34 And so I'll have a comment that says only Jython.

25:36 And then I know why it's been excluded.

25:38 That's cool.

25:40 Because I can just make a list of a dozen regexes and it's all there.

25:44 You put it into that configuration file.

25:46 Yeah.

25:46 Yeah.

25:46 Nice.

25:47 Another thing that I thought was interesting was sort of the converse of this is to explicitly include some files.

25:56 Because if you say, look here, and you run this one particular file, it only looks at the actual files that were loaded, the modules that were loaded, not the stuff laying next to it that maybe should have been reported on but nobody ever touched.

26:09 Right.

26:10 And that was one of the failings of early versions of coverage.py was that the only thing it knew about your code is code that got run.

26:19 And so, for instance, if there was a particular file in your source tree that was never executed at all, I mean, forget about lines not being executed.

26:26 The entire file was never executed.

26:28 It wouldn't show up in the coverage report because coverage had never heard about it.

26:32 Right.

26:33 If you run a line of code in a file, coverage knows about the file and then it can see all the lines that weren't run.

26:37 But if you never ran any of them, coverage never heard of the file.

26:41 So that feature is now in coverage.py.

26:43 If you give it a source option, then it has a tree to search and it can look for all of the importable Python files that it never heard of and tell you about those 0% files.

26:52 Right.

26:52 That's kind of like the example of me saying, here's this method that was never run.

26:56 And, like, not even the module is imported in the main bit of code.

26:59 Right.

27:00 Right.

27:00 Right.

27:00 And, by the way, there's a really cheap, low-tech way to do file-level coverage, which is you delete all your .pyc files and then you exercise all your code.

27:13 And any .py file that doesn't have a .pyc file was never imported.

27:16 Oh, right.

27:17 Yeah.

27:17 Okay.

27:17 That's pretty interesting.

27:18 Very low-tech.

27:19 It's quite low-tech.

27:21 I forgot to challenge the premise of your earlier question.

27:23 Yeah.

27:23 Yeah.

27:23 Let's get back to that.

27:24 Yeah, so you said you don't want to do coverage measurement of your tests, but it actually can be very useful to do coverage measurement of your tests, if only because the way test runners work, it's really easy to make two tests that accidentally have the same name.

27:39 You know, oh, I like that test.

27:41 I want to do one kind of like it.

27:42 I'll copy it and I'll paste it.

27:43 I'll forget to change the name.

27:44 And now I actually only have one test.

27:47 If I look in the code, it looks like there's two, but there's really only one.

27:51 Yeah, yeah.

27:51 It's so easy to do that.

27:53 And so if you do coverage measurement of your test files also, then you'll see those cases.

27:58 Interesting.

27:59 Okay.

27:59 I guess, yeah, I never really thought about that.

28:01 That's pretty valid.

28:02 You know, I was thinking more of like you might say like ignore a particular test and you don't want that to say break the build because it drops it below some percentage or something like that.

28:12 But yeah, that's a very – because I feel test code is probably some of the most copy and pasted code there is.

28:18 Exactly.

28:19 Exactly.

28:19 And you never actually use the function name directly.

28:22 So you'd never know.

28:24 Right.

28:24 The name of the test function doesn't matter.

28:26 Yeah, exactly.

28:28 It's really easy to lose a test.

28:30 All right.

28:30 I accept defeat on this one.

28:33 No, that's a really good point.

28:34 All right.

28:35 Well, spur one for me.

28:36 The other thing, when people say they want to exclude their tests from coverage, often it's because they've set a goal for their coverage measurement.

28:44 Like we need 75% coverage.

28:47 And those goals are really completely artificial.

28:50 Like how did you choose 75%?

28:52 Like why – like a quarter of your code doesn't need to be tested.

28:55 Why is that okay, right?

28:56 So the way I look at it, the number – the coverage number has no meaning except that lower numbers are worse.

29:04 That's the only meaning to the number.

29:06 So if someone says like how much coverage should I have, there's no right answer to that.

29:11 Yeah.

29:12 You know, I guess probably your test code has a pretty high coverage rate relative to your other codes.

29:18 Yes.

29:18 You're only helping yourself in that number.

29:20 That's right.

29:21 That's right.

29:21 You can gain the system.

29:22 Exactly.

29:23 I guess one of the reasons I was thinking about excluding it is I just don't want to see it in the report.

29:27 Like I don't need to see the test coverage.

29:29 But your example of this copy and paste error actually is pretty valid, I think.

29:33 Well, another option in the coverage.py reports is to exclude files that are 100%.

29:40 Right.

29:41 Which, again, lets you focus in on where the problems are.

29:43 Like you don't need to think about files that have 100% coverage.

29:46 What you need to think about is the ones that are missing some coverage because you need to go and look at those lines and write some tests for those files.

29:52 So if all your tests have 100% coverage, then include them and exclude the 100% files from the report.

29:58 Right.

29:59 And hopefully that does a smaller list.

30:01 Yeah.

30:02 Yeah.

30:03 Yeah.

30:04 You can always use the pragma stuff on, say, your test code to say, Well, these three parts I'm having a hard time getting to run for whatever reason.

30:12 And just, you know, tell it to not report on that.

30:14 It'll hit it to 100 and it drops out of the list, right?

30:16 Right.

30:17 Exactly.

30:17 Yeah.

30:18 The other thing about test code I find is that in a full, mature test suite, you've got a significant amount of engineering happening in your test.

30:27 If not in the tests themselves, in the helpers that you have written for your tests.

30:30 Yeah.

30:31 And not that there's code in there that isn't being run and should be run, but there might be code in there that isn't being run and therefore you can delete it.

30:40 Right.

30:40 Yeah.

30:40 That same conversation of like, let's, I do feel like a lot of times people treat their test code with less, what's the right word?

30:48 Kind of professionalism or attention.

30:50 They're like, well, this is test code.

30:52 So it doesn't matter that this big block of code was repeated 100 times.

30:57 Why would I ever extract the method to that?

30:59 Like there's just less attention to the architecture and patterns there.

31:02 And I feel like that would help.

31:04 Right.

31:04 And so I agree with you that repetition should be removed from tests as it is from elsewhere.

31:10 But I've also heard people feel passionately that tests should be repetitive, that each test should be readable all by itself.

31:18 So I'll, you know, give them the benefit of the doubt that maybe that's what they want.

31:22 And that's fine too.

31:24 Yeah, sure.

31:25 And if that's a conscious decision, then that's fine, I think.

31:29 But a lot of people just do it because, well, they wrote one test and then they copied it and then they edited it and they copied it and they edited it.

31:35 You know what I mean?

31:36 Yeah, exactly.

31:37 Right.

31:37 And they don't have time to make the tests nice because who cares about the tests?

31:40 Yeah, exactly.

31:41 Until you change the thing under test and all of a sudden it's so hard to get it to run because you had poor decision making around writing the test.

31:50 Then you claim unit testing is too hard because I don't want to do it and so on.

31:55 Yeah, writing tests is real engineering with different problems than writing your product code.

32:01 And those problems need to be paid attention to, which that's probably a whole other episode.

32:06 Yeah, I've certainly heard people make statements like that they don't really understand, you know, things like object oriented programming and other proper design patterns until they started writing tests and trying to make their code more flexible.

32:19 Like, how do I actually get in between the data access layer and my middle tier logic and test that without having a database and things like that?

32:28 Yeah, they really make you think.

32:29 Yeah, they do because it's a second use of your code.

32:32 And your code is going to be way better designed if you consider more than one use of the code.

32:37 Yeah, absolutely.

32:38 Testability is a great topic.

32:39 Yeah, I actually, yeah, I totally agree.

32:42 And I think that, what you just said right there is one of the main reasons to test is the architecture that comes out of it.

32:48 All right, so you spoke a little bit about these config files.

32:50 And in these config files, I can put regular expressions, which will, you know, limit these sections.

32:55 Oh, and one point I did want to make really quick about that.

32:59 When you put one of those comments, if you put that on like a branch or some kind of structure, like a class, like everything underneath that will be blocked.

33:07 You don't have to like put that on 100 lines, right?

33:09 You put it at the sort of root node.

33:10 Yeah, exactly.

33:11 And it's, so it's basically if you put it on a line with a colon, then that entire clause is excluded.

33:18 The one thing that sounds like it might be a generalization of that that doesn't work is to put one of those comments at the top of a file.

33:23 It doesn't exclude the entire file.

33:25 There's a request to do that.

33:27 That seems like a good idea, but we've never, haven't gotten to that yet.

33:30 Okay, cool.

33:30 So, but back to config files, there's more stuff that you can put in there.

33:34 Like what are useful things that are people are doing there beyond just exclusion?

33:38 Yeah, so there's some basic options.

33:40 Like one of the things that coverage.py can do is to measure not just which statements got executed, but which branches got taken.

33:46 So, for instance, if you write an if statement, it can tell you whether both the true case and the false case were executed.

33:53 And you might say, well, I can tell that by looking at the code in the true case and the code in the else clause, but not every if statement has an else clause.

34:01 So, if you have an if with a statement in it, but there's no else clause, you can't tell just by looking at individual lines that are executed whether the false case of the if was executed.

34:12 Right.

34:12 Did you effectively skip that if block?

34:15 Right.

34:15 Have you ever actually skipped that statement in the if?

34:18 Yeah.

34:19 And so, and branch coverage is what can do that.

34:21 And so, that's one of the options you can set in the config file as well as on the command line.

34:25 I mean, basically, just to go back to the plugins question, the original reason I wrote support for the coverage RC was because I was adding features to coverage and people were using the test runner plugins as their UI.

34:39 So, I didn't have any way to give them to try new features and coverage until the plugins were updated.

34:45 I see.

34:46 So, I added support for an RC file so you could control coverage even under a plugin from a thing that I could actually add features to.

34:53 So, all of the features of coverage are controllable from the RC file.

34:58 A big thing that gets put in there, one of the complicated scenarios for coverage is if you have tests that run in parallel.

35:06 Either because you're running them on separate machines or you're just running them in separate processes or because you ran the 2.7 tests separately from the 3.6 tests.

35:15 And then you want to take all that data and combine it back together to get one coverage report.

35:19 And under those scenarios, there's often cases where, oh, on my CI system, the code was in this directory.

35:25 But back home where I'm going to write the report, it's all in this directory.

35:30 And coverage has to somehow know that those two directories are the same in some way, that they're equivalent.

35:35 And those file path mappings go into the coverage RC file, for instance.

35:40 I see.

35:41 Okay, that's cool.

35:41 So, that during the combination process, it can remap file names to get everything to make sense.

35:47 Yeah, that makes a lot of sense.

35:48 So, speaking of stuff in parallel, what's the story around like threading, async.io, multiprocessing, or even if I just want to start a subprocess?

35:56 Yeah.

35:57 Does it have support for that?

35:58 Do I have to do things special for that?

36:00 Yeah, so that gets complicated, too.

36:02 So, there are four kinds of concurrency that coverage.py supports right out of the box.

36:08 Threading, multiprocessing, gevent, and green.

36:12 I forget which one of the other ones.

36:14 I forget what it's called.

36:14 And there's code in coverage.py that's specifically designed to see that that's happening and do the right thing.

36:22 You have to tell coverage which one you're going to use, but once you do that in your coverage RC, it knows how to do that.

36:28 If you're running your own subprocesses, it gets a little bit trickier because you've got Python code in your main process, and then you're going to spawn a subprocess, which is a whole new Python process that's sort of jumped outside of what coverage is watching.

36:41 There's a little bit of support for coverage getting started on that subprocess.

36:46 You have to do some manual setup, and that's covered in the docs.

36:49 I would like to make that more automatic, but it feels a little intrusive to sort of have coverage start on every Python process you ever start in the future.

36:58 I'd rather be conservative about that than suddenly be in the middle of something where people didn't expect it.

37:05 So, we try to support all those different concurrencies.

37:09 I just got a report that QT threads don't work, which doesn't surprise me because they're C threads, and so how do I get involved in that?

37:16 Right, it doesn't carry that process across, yeah.

37:18 Right, and it gets very fiddly.

37:19 Some of the worst code in coverage.py is in the way we support those kinds of concurrencies because we need to get involved at the very beginning of a thread or the very beginning of a process,

37:31 and there isn't always support for me to just say, hey, next time you start a process, why don't you run a little bit of my code first?

37:37 No, that's not your process.

37:39 Yeah, we do some very invasive things there.

37:42 If you're interested, go and look at multiproc.py.

37:44 Yeah, how interesting.

37:46 This portion of Talk Python To Me is brought to you by Manning.

37:51 Python has become one of the most essential programming languages in the world with a power, flexibility, and support that others can only dream of,

37:58 but it can be tough learning it when you're just starting out.

38:01 Luckily, there's an easy way to get involved.

38:04 Written by MIT lecturer Annabelle and published by Manning Publications,

38:08 Git Programming, learn to code with Python, is the perfect way to get started with Python.

38:12 Anna's experience as a teacher of Python really shines through as you get hands-on with the language without being drowned in confusing jargon or theory.

38:20 Filled with practical examples and step-by-step lessons, Git Programming is perfect for people who want to get started with Python.

38:26 Take advantage of a Talk Python exclusive 40% discount on Git Programming by Annabelle.

38:32 Just visit talkpython.fm/manning and use the code belltalkpy.

38:37 That's belltalkpy, all one word.

38:41 One thing that the documentation talks about is this thing called sitecustomize.py.

38:46 Right, exactly.

38:47 I had never even heard of this.

38:49 You're like, oh, you just put it in here.

38:50 I'm like, what is this?

38:51 Tell them about this.

38:53 It's all sort of the start of the initialization of Python itself, right?

38:56 Right, exactly.

38:57 So this is about how do, if you're going to run a Python program, how can I make it so that my code runs before your program even starts?

39:05 Right, because if you're going to run a subprocess and it's a Python program, I want coverage to start before your code starts.

39:12 One way to do that is for you to change your code so that instead of launching your Python program, you launch it with coverage.

39:18 But that gets very invasive.

39:20 No one wants to do that.

39:21 You're not going to run your product by launching coverage, so your test would have to be different.

39:26 Probably not.

39:26 Product works.

39:28 Yeah.

39:28 So I looked around for ways to have code run before your main program.

39:34 And there's no sort of built-in support for it.

39:38 Perl actually has a command line switch that says run this program, but first run something else.

39:44 Python doesn't.

39:45 So there are two ways to do it.

39:46 One is that when you run a program in Python, if it finds a file called site, customize.py, it will run it.

39:52 And I don't know exactly what that file is for.

39:54 It sounds like the kind of thing that would be recommended against these days.

39:59 Seems weird.

40:00 Like if you need something for your program, right?

40:02 Don't put it into a weird file in your site packages.

40:05 Somehow put that in your main program.

40:07 But it's there.

40:08 So one of the ways to get coverage to run before your subprocess starts is by putting something inside

40:13 customize.py.

40:14 And can you make that just like a file alongside your working directory, the top level of your

40:19 working directory?

40:20 Or has it got to go somewhere else?

40:21 Honestly, I'm not quite sure.

40:22 When I have to do this, I use the second technique for doing it because changing a file is scarier

40:30 than creating a new file.

40:32 And so the second way to do it only involves creating a new file, even though it's perhaps

40:38 an even more obscure way to get code to run before the start of Python.

40:42 Now, we don't have to go through all the details.

40:44 But if you go into your site packages directory and you look for .pth files, path files, they

40:50 have this very bizarre semantic, which is if a line in that file starts with the word import,

40:56 then it will execute that line, even if the line has way more stuff than just an import

41:01 statement.

41:01 Weird.

41:01 Yeah, it's super weird.

41:03 It's super weird.

41:04 And you can name it anything?

41:05 Just like?

41:06 Yeah, anything .pth.

41:07 Yeah.

41:07 This is all part of how site packages and the path gets set up.

41:11 Just a little bit of backstory.

41:13 Working at Coverage is fascinating because just programming technology is interesting,

41:17 but you also get to discover all sorts of really weird, dark corners of the Python world.

41:22 And I've gotten in the habit of every time a new alpha of CPython is announced, I get it

41:29 as soon as I can, and I build it, and I run the Coverage test suite.

41:33 And some of the core developers are used to, like, we better get the alpha out there so that

41:38 Ned can run the Coverage test suite and tell us what we broke.

41:40 So I think 3.6 RC3 was because of me.

41:44 Oh, wow.

41:45 Because of a bug I reported from the Coverage.py test suite.

41:47 Yeah, there's a lot of weird, dark corners and a lot of kind of gross hacks to make things

41:52 work.

41:52 It's very difficult.

41:53 So for instance, I said Coverage run works just like Python.

41:56 Well, it's not easy to make a program that will run your Python program just the way Python

42:02 runs your Python program.

42:03 And there's some extensive tests in the Coverage.py test suite that actually do run the two side

42:08 by side and then do a bunch of comparisons of the environment in which the code finds itself

42:12 to try to assert that it does run it the same way.

42:15 Yeah.

42:16 I don't envy the job of keeping that compatibility working.

42:19 Yeah.

42:20 Well, luckily, we have a good test suite.

42:22 Yeah.

42:23 Well, I bet it has good code coverage as well.

42:26 Yeah.

42:26 Well, the sad thing is that there's code inside Coverage.py that because it's at the very

42:31 heart of how coverage measurement gets done cannot itself be coverage measured.

42:35 So my code coverage is at about 94%.

42:38 That's still pretty good.

42:39 But yeah, that's still pretty good.

42:40 That's quite ironic.

42:41 It is ironic.

42:42 You'd think like me of all people, I'd have 100% test coverage.

42:45 But and I've thought about really weird, hacky ways of trying to get at that stuff.

42:49 But it's just not worth it.

42:50 Yeah, I totally hear.

42:51 So you spoke a little bit about the complexities and challenges of making it work.

42:55 Let's dive in a little bit to how this actually works, right?

42:57 Yeah.

42:58 It seems like magic that I type your command line thing and then numbers all spit out of,

43:05 well, here's exactly how your code ran.

43:07 Like, how does that work?

43:08 Yeah.

43:09 So at the very heart of it is a feature of CPython called the trace function.

43:13 So if you look in the sys module, there's a function called set trace.

43:16 And you give it a function and it will call your function for every line of Python that gets

43:22 executed.

43:23 And that function can do whatever it wants.

43:25 It is the basis for debuggers, for profilers, and for code measurement tools.

43:31 And for some other things like tools that will let you run your program and have it just print

43:36 every line of code that gets run.

43:37 So you can sort of get a like a global log of everything that happened.

43:41 Right.

43:42 Some of those like sort of inspectors that will print out like an execution of your code as

43:47 it runs, like the actual lines that are running.

43:49 Yeah, those are pretty neat.

43:50 Yeah, exactly.

43:50 Yeah.

43:50 Doug Hellman wrote a cool one called Smiley.

43:52 Smiley.

43:53 Okay.

43:53 It does some cool things.

43:54 Yeah.

43:54 It spies on your code.

43:56 So at the heart of it is that trace function.

43:59 And for instance, if you've ever had to break into a debugger from your code and you type

44:03 import PDB, PDB.setTrace, the reason it's called .setTrace instead of what it should be called,

44:08 you know, break into the debugger, is because that's the function where PDB calls setTrace to get its trace

44:15 function in place so that it will get told as lines get executed and then you're debugging.

44:20 So that's the core CPython feature.

44:22 And you can go and write, you know, the 10 lines of code that do interesting stuff with the trace function.

44:28 It's actually pretty simple.

44:29 Coverage.py has way more lines of code than that.

44:32 But, you know, at its heart, that's what it's doing.

44:35 It sets a trace function and then it runs your code.

44:38 And as its trace function gets invoked with, you know, this line got executed, this line get executed, etc., etc.,

44:44 it records all that data and dumps it into a data file.

44:47 And that's the run and out phase of Coverage.py.

44:50 All that raw data then gets picked up when you say Coverage report.

44:54 It reads that data.

44:56 It looks at your source to analyze the source to figure out what could have been run.

45:00 Right in that first phase, all we hear is what got run.

45:03 The analysis phase is let's look at the source code.

45:06 How many lines are there?

45:07 What could get run?

45:08 And then essentially it just does a big set subtraction.

45:11 Here's the lines that could have been run.

45:13 There are the lines that did get run.

45:14 What's left over are the lines that didn't get run.

45:17 I mean, conceptually.

45:18 One thing that you did talk about in how it works is in the documentation is that you actually use the PYC files as part of this, right?

45:27 You've got to look in there for the line numbers and stuff, which is kind of interesting.

45:32 And that's one of the things that's actually changed a number of times over the course of Coverage.py's life is, well, how do we know what could have been executed?

45:42 The question of what did get executed is kind of straightforward because we get it from the trace function.

45:46 There's not much we can do there.

45:48 I mean, there's a lot to do there.

45:50 But there's essentially only one way to know what got run.

45:53 Figuring out what could have been run, there's a bunch of different ways.

45:56 As you mentioned, .pyc files compiled into them are a line number table that tells Python which lines are executable.

46:05 And that's how Python actually decides when a next line has been run.

46:10 The trace function, it's executing bytecodes.

46:12 It calls the trace function when the line number table says this bytecode is the first bytecode on a new line.

46:17 Right, because if I write like print, you know, quote, ned, comma, quote, batch elder, that actually is like multiple steps of the instruction.

46:28 If I disassembled that, that would be like load the first string onto the stack, load the second string, execute the function, get the return value, all that type of stuff, right?

46:36 That's right.

46:36 So the trace function only gets called for lines.

46:39 And so we're looking at the same information the Python interpreter is for deciding where the lines are.

46:43 It gets more involved in that because, for instance, for branch coverage, we have to decide where the branches are.

46:48 And we do that by analyzing the abstract syntax tree.

46:52 We used to do it by analyzing the bytecode back when I thought, oh, well, the bytecode will have all the ifs and jumps I need.

46:58 But it doesn't, and it never did.

47:01 And when the async keywords got added, they were completely different than everything else.

47:06 And I said, OK, fine, we're getting rid of all this bytecode analysis.

47:09 And I'm going to do an AST analysis because I understand the AST when I don't understand the bytecode.

47:13 All right.

47:13 So it does support async and await?

47:15 Yeah.

47:16 You know, I have to be honest.

47:17 When that first came out, I didn't know anything about async and await.

47:20 I didn't understand how to write programs that use them.

47:24 And I sort of took the low-tech, lazy maintainers approach, which is I'll wait for the bug reports to come in about how it doesn't work for those things.

47:31 And no one has ever said it doesn't work.

47:33 So I guess it works.

47:34 Yeah.

47:35 All right.

47:35 That'll do it.

47:36 Yeah.

47:37 Cool.

47:37 So I guess one question is calling functions in Python is not one of the fastest things that Python does relative to, say, other languages.

47:46 So if you're calling this set trace function on every single line, how does that not just stop the execution, basically?

47:52 Yeah.

47:52 So, well, so the really simple answer is that if you write a Python function and set it as your trace function, then, yeah, you're going to have a significant performance hit.

48:01 Because it's going to call a Python function for every line of your code.

48:05 And if that Python function does anything interesting at all, then it's going to do a lot of work for every line of your code.

48:11 Inside Coverage, we actually have two implementations of the trace function.

48:15 One in Python and one in C.

48:17 And the one that's in C is there to make it go faster.

48:19 So there's a bunch of work to try to do as little work as possible on each call.

48:25 So, for instance, when we get told that we're calling a new function, we do a bunch of work to figure out is this function or is this file, rather, a file that we're interested in at all.

48:37 Have you already figured out how much coverage it has?

48:39 Like if it's 100, right, then don't do it again.

48:41 Well, we don't know.

48:42 At this point, we're in the run phase.

48:44 We have no idea about numbers like that.

48:46 All we know is this file is getting executed.

48:49 Is our current configuration telling us that that file is interesting or it's not interesting?

48:53 And if it's not interesting, then we try to quickly get out of that function and set some bookkeeping so that the function doesn't get called again until we return from the function, for instance.

49:03 So there's a lot of work to try to make the trace function as fast as possible.

49:07 Because especially for mature test suites for the types of people that are running coverage.

49:13 The one thing I can tell you about all of those test suites is that developers wish they ran faster.

49:18 Like I don't need to know anything about your test suite.

49:20 If you've got a lot of tests, you want them to run faster.

49:23 So the last thing I want to do is make them go even slower.

49:27 And I don't know what the typical overhead is of coverage on a test suite because it's going to vary so much depending on what else those tests are doing.

49:35 But the C code is there to try to make it go as fast as possible.

49:38 I see.

49:39 Yeah, that makes a lot of sense.

49:40 The pure Python implementation is there for, for instance, PyPy, which can't run C extensions.

49:45 Right.

49:45 But after a while, it'll start to speed up as they maybe consider it has to be jitted after like a thousand lines or something.

49:52 I guess so.

49:53 I haven't.

49:54 I don't know.

49:54 PyPy is still under the magic category for me.

49:57 And I don't know whether a trace function will actually get the jit applied.

50:02 That's the thing I am used to is that a trace function is not run like regular code.

50:08 And I don't know if PyPy can jit a trace function, for instance.

50:13 I have no idea either.

50:15 Yeah, I don't know.

50:16 Interesting.

50:17 There are a few speed ups in there specifically for PyPy.

50:20 Basically, when a PyPy developer tells me, hey, why don't you say this magic thing that you don't understand?

50:25 And PyPy will go a little bit faster.

50:26 And I'm like, great.

50:27 Sure, I'll put it in.

50:28 Yeah, PyPy is interesting.

50:32 So I guess, you know, that's a good segue over to which runtimes are supported.

50:36 Like, you mentioned jiton, you mentioned PyPy, obviously cpython.

50:40 What versions of cpython?

50:42 What else?

50:42 Yeah, so the current released version of coverage.py is 4.5.1.

50:47 And that supports Python 2.6 and Python 3.3 and up.

50:53 So 2627, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37.

50:58 The tip of the repo now, I'm already working on coverage 5.0 alphas.

51:03 And I've dropped support for 2.6 and for 3.3.

51:06 But the released version can do 2.6.

51:09 For a while, I was very proud of supporting 2.3 through 3.3, which is kind of an interesting trick.

51:16 But I don't have to do that anymore.

51:18 So PyPy, both 2 and 3, are supported.

51:21 I have run tests on jiton and IronPython.

51:24 They can't do all of it because they can't do the analysis phase because they don't have AST.

51:28 But you can run your code under jiton and IronPython for the measurement phase.

51:34 And then you use cpython to do the analysis phase.

51:36 I see.

51:37 I don't know how well that works.

51:38 I haven't heard a lot from people about it.

51:40 I don't know how much those jiton and IronPython are getting used these days.

51:44 There's another one called python.net.

51:45 I actually haven't used it for anything.

51:47 But I think it's a successor type of thing.

51:49 A little bit different than IronPython, but similar.

51:51 Is it?

51:52 I need to look into this.

51:53 I need more complication in my life.

51:55 Yeah, I haven't done a lot with it.

51:58 But python.net seems like a more maintained, different take on what IronPython was.

52:04 But I pretty much have exhausted my knowledge of it now.

52:07 All right.

52:07 Cool.

52:07 My question earlier was, what are your plans on supporting old versions?

52:11 So if cpython stops supporting 2.7, are you going to stop supporting it?

52:17 Yeah, that's certainly going to happen soon enough.

52:19 Or say 3.4, what's the timing?

52:23 Do you try to stay farther behind?

52:24 What's the thing?

52:26 Like I said at the top of the show, I'm pretty inertial.

52:29 So I tend to support things for longer.

52:31 So my philosophy about coverage.py development is that I want coverage.py to be available

52:37 for anyone who's trying to make their code work better for Python.

52:42 And the environments they care about, I will care about.

52:46 So for instance, I first ported coverage.py to 3.0 in 2009, which was pretty early.

52:54 And it was pretty rough around the edges.

52:55 But I thought, you know, if people are going to start porting their libraries to Python 3,

52:59 it'd be super useful if coverage.py were there to help them understand how their tests were doing.

53:04 So I tried very hard to get ahead of it.

53:06 And for that reason also, coverage.py has no installation prerequisites.

53:10 Because if I prerequire a library, then that library has to get into a new environment before coverage.py can.

53:17 And then we've got a chicken and egg problem.

53:19 Yeah.

53:20 It also gives me a principled reason to have written my own HTML template engine, which is fun.

53:26 That sounds like a pretty challenging thing.

53:28 Also challenging.

53:30 Another runtime, if you want to call it that, I guess, that seems interesting is Cython.

53:36 Does this have any...

53:37 But it seems to me my first guess is it wouldn't work with Cython.

53:40 But what's the story there?

53:41 I should really know more about Cython.

53:43 And in fact, it's been proposed to me that instead of writing C code for the trace function,

53:47 I should write Cython for the trace function, which I've just been resistant to because, like I said, I'm inertial.

53:54 So my understanding of Cython is that it compiles to C code.

53:57 And then when you're running, you're running C code.

53:59 So you need a C coverage measurement tool in order to understand what's happening there.

54:04 Yeah.

54:05 It compiles to a C file, which then compiles, like at least on Mac, to a .so file.

54:10 And the .so file is running.

54:12 Yeah.

54:12 Right.

54:12 Coverage.py won't be able to see any of that execution.

54:15 A C coverage tool could.

54:17 But then you'd have to figure out how to map that back to the Cython code that you're actually interested in.

54:24 Which actually brings up an interesting point.

54:25 One of the things that coverage.py has gotten in its 4.0 releases is plugins so that you can do coverage measurement of things that are not directly Python but result in Python.

54:39 So, for instance, there's a Django coverage plugin that can measure the coverage of your Django templates.

54:46 Because Django templates themselves have if statements and for loops in them.

54:51 So that's code.

54:53 You'd like to know if there's coverage there.

54:55 And so there's a plugin, the Django coverage plugin, that works with coverage.py to basically understand how Django executes the templates.

55:04 And take the raw Python information about the template execution and map it back to the lines in the Django template.

55:12 So that you can get sort of a red-green Christmas tree of your Django template.

55:18 Oh, that's cool.

55:19 Yeah, it's very cool.

55:19 And it was getting a little stale, but I've just gotten a new maintainer to take it over.

55:24 And so they just had a release today, actually.

55:26 Oh, great.

55:27 Yeah.

55:27 All right.

55:28 That's interesting.

55:28 It seems to me like there's probably enough information there, but that it's really not super straightforward.

55:33 For Cython.

55:34 But maybe plugins would do it.

55:36 Yeah.