anywidget: Jupyter Widgets made easy

Episode Deep Dive

Guest Introduction

Trevor Manz is a software engineer at Marimo, a next-generation Python notebook platform. Before joining Marimo, Trevor completed his PhD in data visualization at Harvard Medical School, where he built tools for biological scientists to explore large genomics and spatial genomic datasets. His research focused on bridging the gap between sophisticated web-based visualization tools and the Python notebook environments where scientists actually work. This frustration with the complexity of building interactive widgets that work across multiple notebook platforms led him to create anywidget. Trevor's background spans both the web development and Python ecosystems, giving him unique insight into how these two worlds can work together more seamlessly.

What to Know If You're New to Python

This episode explores interactive computing and data visualization in Python notebooks. Here is some background that will help you get the most from this discussion:

- Jupyter Notebooks are interactive documents that let you write Python code, run it, and see results (including visualizations) all in one place - they are widely used in data science and scientific computing

- Widgets in notebooks are interactive UI elements (like sliders, buttons, or charts) that let you manipulate data visually rather than just writing code

- The discussion references data frames frequently - these are table-like data structures (rows and columns) commonly used in pandas and Polars for data analysis

- Understanding the concept of a kernel is helpful - it is the background Python process that executes your notebook code and maintains your variables in memory

Key Points and Takeaways

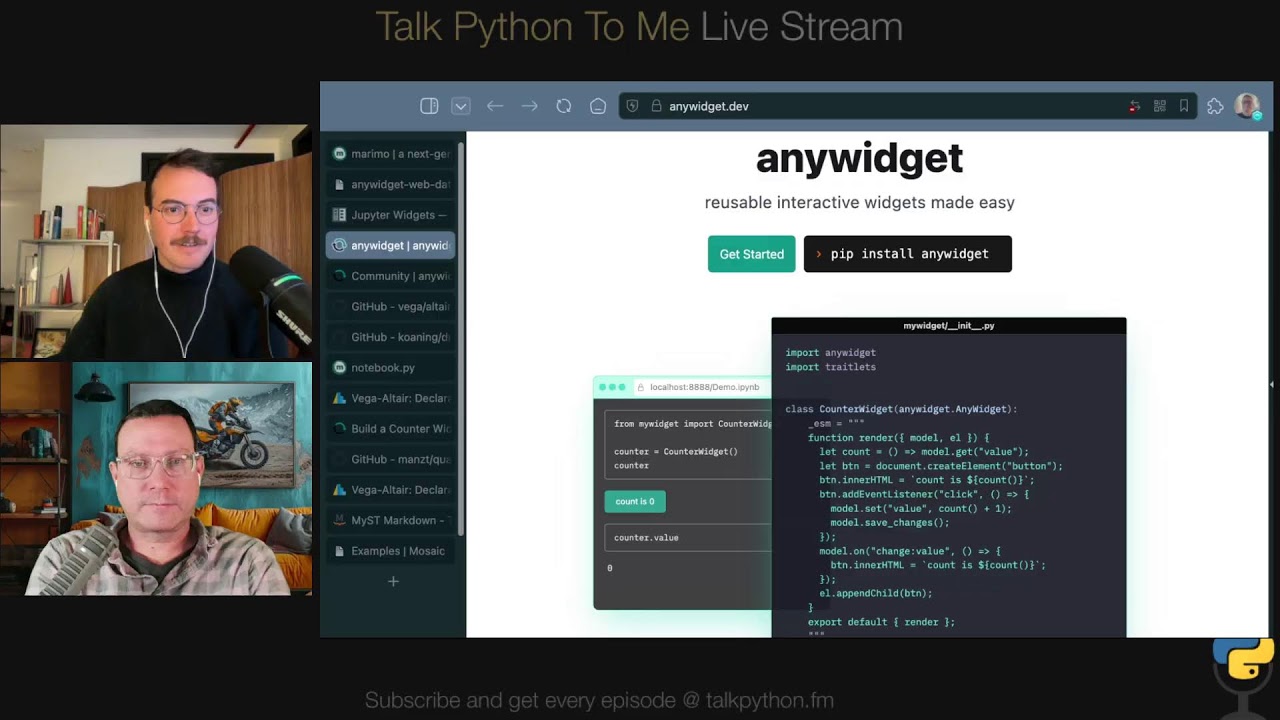

1. anywidget Simplifies Building Interactive Notebook Widgets

anywidget is a Python library that dramatically simplifies the process of creating custom interactive widgets for computational notebooks. Before anywidget, building a widget that worked across Jupyter, Google Colab, VS Code, and other platforms required publishing to both PyPI and NPM, managing complex JavaScript toolchains, and writing platform-specific adapters. anywidget eliminates this complexity by letting developers define both the Python backend and JavaScript frontend in a single Python class, using standardized ES modules that work everywhere. The result is that widget authors can now focus on their visualization logic rather than wrestling with build systems and platform quirks.

- anywidget.dev - Official documentation and getting started guide

- github.com/manzt/anywidget - Source code and community contributions

2. The "Just Enough JavaScript" Philosophy

Trevor designed anywidget around the principle of "just enough JavaScript" - giving Python developers the minimal amount of frontend code needed to unlock web interactivity without dragging in the entire web ecosystem. The JavaScript you write for anywidget is standardized ECMAScript that runs directly in the browser, not a framework-specific dialect that requires transpilation. This means beginners can start by writing simple DOM manipulation code, while advanced users can optionally bring in React, Vue, or Svelte through dedicated "bridges" that adapt those frameworks to the anywidget specification. The entry point stays simple, but the ceiling for what you can build remains high.

- developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/JavaScript/Guide/Modules - ES Modules documentation

3. Widgets Enable Bidirectional Communication Between Visualization and Code

Traditional notebook outputs are one-way: you run code and see a result. Even interactive visualizations like zoomable charts often trap their state in the output - you can see the selection but cannot programmatically access it. Jupyter widgets, and by extension anywidget, enable true bidirectional communication where user interactions (clicking points, drawing regions, adjusting sliders) update Python variables in the kernel. This transforms notebooks from a "write code, view output" loop into a richer environment where gestures and visual interactions become another mode of input alongside typing code.

"I like to think of it as like in a traditional REPL kind of environment, your two modes of input are sort of like writing code and running. So you can write the code and you can run the cell and then you can observe the output but in order to act on something that you see in that output you have to write more code." -- Trevor Manz

4. Marimo Represents Next-Generation Notebook Design

Marimo is a Python notebook platform that takes a different approach from Jupyter by modeling notebooks as directed acyclic graphs (DAGs) rather than arbitrary cell execution orders. When you modify a variable in one cell, Marimo automatically re-executes all dependent cells, eliminating the "hidden state" problem that plagues traditional notebooks. Marimo notebooks are stored as pure Python files (not JSON), making them git-diffable and reproducible. The platform has deep integration with anywidget, recommending it as the standard way for users to extend Marimo with custom UI elements.

- marimo.io - Marimo notebook platform

- github.com/marimo-team/marimo - Marimo source code

5. The Widget Ecosystem Includes Powerful Visualization Tools

Several popular visualization libraries have adopted anywidget as their foundation. Altair, a declarative statistical visualization library, uses anywidget to enable selections that return data frames to the kernel. The draw-data widget by Vincent Warmerdam lets users literally draw data points on a canvas and receive them as a data frame - perfect for teaching machine learning concepts or quickly generating test datasets. Lonboard wraps Uber's deck.gl library for high-performance geospatial visualization, rendering millions of points by leveraging Apache Arrow for efficient data transfer to the GPU.

- altair-viz.github.io - Altair visualization library

- github.com/koaning/drawdata - Draw data widget by Vincent Warmerdam

- github.com/developmentseed/lonboard - Geospatial visualization widget

6. Apache Arrow Enables High-Performance Data Transfer

A growing trend in the anywidget ecosystem is using Apache Arrow for efficient data serialization between Python and the browser. Traditional approaches serialize data to JSON, which becomes painfully slow with millions of rows. Arrow provides a columnar memory format that can be copied directly to the GPU without expensive transformation. Lonboard demonstrates this dramatically: a dataset with 3.5 million rows that previously took minutes to render (or crashed entirely) now displays in one to two seconds by shipping Arrow buffers directly to the frontend.

- arrow.apache.org - Apache Arrow project

- deck.gl - WebGL-powered visualization framework by Uber

7. Building a Widget Requires Just a Python Class and ESM String

Creating an anywidget is remarkably straightforward: you define a Python class that extends anywidget.AnyWidget and specify your frontend code in an _esm class attribute. The frontend code exports a render function that receives two arguments: a model object for communicating with the kernel (using get, set, and save_changes methods) and an element representing the DOM container for your widget. You can write the JavaScript inline as a string for prototyping, or point to an external .js file for production use. This approach means you can develop and iterate on widgets directly in a notebook before packaging them for distribution.

import anywidget

import traitlets

class CounterWidget(anywidget.AnyWidget):

_esm = """

export function render({ model, el }) {

let count = () => model.get("value");

let btn = document.createElement("button");

btn.innerHTML = `count is ${count()}`;

btn.addEventListener("click", () => {

model.set("value", count() + 1);

model.save_changes();

});

model.on("change:value", () => {

btn.innerHTML = `count is ${count()}`;

});

el.appendChild(btn);

}

"""

value = traitlets.Int(0).tag(sync=True)

8. Host Platforms Implement the anywidget Specification

anywidget separates concerns between widget authors and platform implementers through the concept of "host platforms." Widget authors write standardized Python and JavaScript code without worrying about how different environments load and execute that code. Host platforms (Jupyter, Marimo, VS Code, Google Colab, and potentially Myst) implement the underlying communication layer - typically WebSockets - and handle loading ES modules. This separation means that when a new notebook platform emerges, it only needs to implement the anywidget specification once to gain access to the entire ecosystem of existing widgets.

- mystmd.org - Myst markdown for computational documents

9. Mosaic Demonstrates Advanced Architecture Patterns

Mosaic represents an emerging architectural pattern where visualization clients express all their data needs as SQL queries against a database (typically DuckDB). The database can run either in the Python kernel for high-performance compute scenarios or compiled to WebAssembly to run entirely in the browser. This flexibility means the same visualization code works whether you need HPC resources or want to ship a static website where users can drag-and-drop their own CSV files. anywidget has enabled experimentation with these novel architectures by making it easier to prototype the frontend-backend communication layer.

- uwdata.github.io/mosaic - Mosaic visualization system

- duckdb.org - DuckDB analytical database

10. Publishing Widgets Is as Simple as Publishing Any Python Package

Because anywidget bundles both Python and JavaScript code into a standard Python package, publishing to PyPI works exactly like any other library. You can use modern tools like Hatchling (which anywidget's starter template is configured for) along with uv build and uv publish. The JavaScript can live either inline in the Python file or in a separate .js file that gets included in the package. Trevor provides video tutorials walking through the entire process from prototyping in a notebook to publishing on PyPI.

- github.com/astral-sh/uv - Fast Python package manager

- hatch.pypa.io - Modern Python project manager

11. AI and Vibe Coding Accelerate Widget Development

The combination of anywidget's simple JavaScript API and the power of modern AI coding assistants creates a compelling development experience. Since anywidget uses vanilla JavaScript rather than a custom framework, AI models perform exceptionally well at generating and iterating on widget code. Marimo enhances this further with built-in AI chat that can inspect Python variables and include their schemas in prompts, so when you ask for a widget to visualize a specific data frame, the AI knows the column names and types. Vincent Warmerdam's joke that Trevor created anywidget "so that he could make anywidgets" speaks to how accessible widget development has become.

12. The Web and Python Ecosystems Have Evolved in Parallel

Trevor made the fascinating observation that the web and Python have existed for almost exactly the same amount of time - the first webpage appeared around the same year as Python's first release. Both ecosystems have matured significantly, with the web finally standardizing ES modules in 2018 and Python's tooling ecosystem accelerating with tools like uv and Ruff. anywidget bridges these two mature ecosystems by using web standards (ES modules) and Python packaging (PyPI) without requiring developers to navigate the historical baggage of either. What felt like writing legacy code in 2020 now feels modern and streamlined.

Interesting Quotes and Stories

"I want the feeling of being able to author a widget to be very similar to the way that you can copy and paste code into a notebook, but move it into a file. And then you could publish that to PyPI." -- Trevor Manz

"With great power comes great responsibility, but we want to give that to people that want to build these types of integrations." -- Trevor Manz

"I used to type Python code without type hints. Then I started using type hints, and now I can't imagine not having any autocomplete. And now I think like maybe when you start working with data in long-lived sessions, having some of these guardrails actually help you keep on track." -- Trevor Manz on Marimo's constraints

"The state, I like to think of it as is trapped in the output and you can't get it back in the notebook." -- Trevor Manz on traditional non-widget visualizations

"It's shocking. It's more like, oh, I think we're holding ourselves back at times by maybe some of the standard practices versus like, yeah, hardware has gotten very good." -- Trevor Manz on modern visualization performance

"Vincent's joke that he likes to tell is that I created anywidget so that he could make anywidgets." -- Trevor Manz on accessibility of widget development

Key Definitions and Terms

- Jupyter Widget: An interactive component in a notebook that can render custom UI and communicate bidirectionally with the Python kernel, allowing user interactions to update Python variables

- ES Modules (ESM): The official JavaScript module standard (using

import/exportsyntax) that runs natively in browsers since 2018, as opposed to older formats like CommonJS that required transpilation - Kernel: The Python process running behind a notebook that maintains state (variables, imports) and executes code cells

- Host Platform: In anywidget terminology, the notebook environment (Jupyter, Marimo, VS Code, Colab) that implements the communication layer between frontend and backend

- Apache Arrow: A columnar memory format for efficient data interchange, enabling zero-copy data transfer between Python and GPU-accelerated visualization

- WebAssembly (Wasm): A binary instruction format that allows languages like Python to run in web browsers at near-native speed

- Traitlets: A Python library for typed attributes with validation and change observation, used by anywidget to define synchronized state between frontend and backend

Learning Resources

If you want to go deeper on the topics covered in this episode, here are some recommended courses from Talk Python Training:

Data Science Jumpstart with 10 Projects: Learn hands-on data science with Jupyter notebooks, including visualization with Pandas and Plotly - perfect background for understanding the notebook ecosystem that anywidget extends

Python Data Visualization: Explore the Python plotting landscape including Altair, which was discussed as a major anywidget adopter

Reactive Web Dashboards with Shiny: Learn reactive programming concepts that parallel Marimo's approach to automatic cell re-execution

Visual Studio Code for Python Developers: Master the IDE that now has first-class Marimo support through their new VS Code extension

Python for Absolute Beginners: Start here if you are new to Python and want to build the foundation needed to work with notebooks and widgets

Overall Takeaway

anywidget represents a quiet revolution in how Python developers can extend notebook environments with interactive visualizations. By embracing web standards (ES modules) and Python packaging (PyPI) while abstracting away platform-specific complexity, Trevor Manz has created a framework that turns widget development from a multi-week infrastructure project into something you can prototype in an afternoon. The ripple effects are already visible: established libraries like Altair have adopted it, new creative tools like draw-data have emerged, and high-performance visualization with Apache Arrow has become accessible to non-specialists.

Perhaps most importantly, anywidget embodies a philosophy of meeting developers where they are. Python developers can start with minimal JavaScript and progressively learn more as needed. Frontend developers can leverage their existing skills with React or Vue through bridge libraries. AI coding assistants excel at generating anywidget code precisely because it uses vanilla standards rather than custom abstractions. This accessibility, combined with Marimo's vision of reproducible reactive notebooks, points toward a future where the barrier between exploring data and building polished interactive tools continues to dissolve.

Whether you are a data scientist who wants to build a quick custom visualization, a library author looking to add notebook support, or simply curious about the intersection of Python and the modern web, anywidget offers a compelling and surprisingly approachable entry point. The combination of Trevor's thoughtful API design, the growing widget ecosystem, and integration with next-generation tools like Marimo makes this an exciting space to watch - and to participate in.

Links from the show

anywidget GitHub: github.com

Trevor's SciPy 2024 Talk: www.youtube.com

Marimo GitHub: github.com

Myst (Markdown docs): mystmd.org

Altair: altair-viz.github.io

DuckDB: duckdb.org

Mosaic: uwdata.github.io

ipywidgets: ipywidgets.readthedocs.io

Tension between Web and Data Sci Graphic: blobs.talkpython.fm

Quak: github.com

Walk through building a widget: anywidget.dev

Widget Gallery: anywidget.dev

Video: How do I anywidget?: www.youtube.com

PyCharm + PSF Fundraiser: pycharm-psf-2025 code STRONGER PYTHON

Watch this episode on YouTube: youtube.com

Episode #530 deep-dive: talkpython.fm/530

Episode transcripts: talkpython.fm

Theme Song: Developer Rap

🥁 Served in a Flask 🎸: talkpython.fm/flasksong

---== Don't be a stranger ==---

YouTube: youtube.com/@talkpython

Bluesky: @talkpython.fm

Mastodon: @talkpython@fosstodon.org

X.com: @talkpython

Michael on Bluesky: @mkennedy.codes

Michael on Mastodon: @mkennedy@fosstodon.org

Michael on X.com: @mkennedy

Episode Transcript

Collapse transcript

00:00

00:07

00:10

00:13

00:15

00:22

00:29

00:35

00:57

01:03

01:04

01:08

01:10

01:13

01:16

01:20

01:23

01:24

01:27

01:32

01:37

01:40

01:46

01:51

01:53

01:57

02:01

02:08

02:12

02:15

02:22

02:25

02:29

02:30

02:36

02:37

02:48

02:52

02:57

03:02

03:07

03:12

03:18

03:25

03:32

03:38

03:43

03:48

03:51

03:53

03:55

03:57

04:03

04:07

04:11

04:16

04:20

04:23

04:24

04:26

04:27

04:30

04:31

04:32

04:39

04:43

04:49

04:54

04:59

05:03

05:07

05:08

05:11

05:20

05:25

05:27

05:30

05:34

05:39

05:42

05:47

05:56

05:58

06:08

06:11

06:14

06:15

06:15

06:17

06:22

06:22

06:25

06:25

06:26

06:30

06:33

06:35

06:40

06:40

06:42

06:46

06:50

06:54

06:58

07:02

07:08

07:13

07:18

07:25

07:27

07:32

07:36

07:38

07:40

07:42

07:46

07:48

07:50

07:54

07:58

08:01

08:06

08:10

08:15

08:18

08:22

08:28

08:31

08:34

08:36

08:38

08:43

08:44

08:46

08:49

08:51

08:56

08:59

09:03

09:09

09:13

09:16

09:18

09:23

09:28

09:30

09:39

09:44

09:49

09:55

10:01

10:07

10:13

10:21

10:28

10:33

10:39

10:43

10:48

10:52

10:58

11:04

11:11

11:17

11:22

11:28

11:33

11:39

11:44

11:49

11:52

11:58

11:59

12:01

12:02

12:03

12:04

12:05

12:05

12:10

12:11

12:14

12:17

12:18

12:25

12:32

12:37

12:43

12:48

12:50

13:00

13:07

13:11

13:11

13:17

13:42

13:46

13:48

13:50

13:56

13:59

14:03

14:06

14:16

14:19

14:25

14:26

14:29

14:34

14:38

14:43

14:48

14:51

14:56

15:00

15:02

15:06

15:07

15:11

15:13

15:19

15:23

15:27

15:30

15:34

15:35

15:37

15:41

15:48

15:54

15:58

16:02

16:04

16:08

16:10

16:11

16:13

16:19

16:25

16:30

16:33

16:38

16:44

16:47

16:51

16:54

16:58

17:02

17:06

17:08

17:10

17:14

17:17

17:20

17:21

17:27

17:30

17:33

17:34

17:37

17:38

17:44

17:47

17:54

17:57

18:02

18:04

18:06

18:10

18:14

18:16

18:25

18:28

18:32

18:35

18:36

18:38

18:45

18:47

18:47

18:50

18:50

18:53

18:56

18:56

19:02

19:08

19:13

19:18

19:24

19:29

19:34

19:40

19:44

19:45

19:46

19:48

19:52

19:55

20:02

20:04

20:08

20:11

20:13

20:19

20:31

20:36

20:44

20:49

20:57

21:06

21:16

21:22

21:24

21:25

21:30

21:32

21:38

21:40

21:42

21:44

21:45

21:47

21:50

21:53

21:58

22:05

22:12

22:18

22:23

22:26

22:31

22:36

22:42

22:46

22:50

22:54

22:59

23:05

23:11

23:17

23:21

23:27

23:35

23:40

23:45

23:50

23:56

24:00

24:05

24:10

24:15

24:19

24:24

24:29

24:33

24:38

24:44

24:51

24:56

25:00

25:04

25:09

25:14

25:18

25:21

25:21

25:26

25:27

25:28

25:35

25:38

25:42

25:43

25:47

25:49

25:54

25:57

26:01

26:03

26:10

26:12

26:22

26:23

26:23

26:27

26:27

26:30

26:32

26:36

26:37

26:42

26:49

26:54

26:59

27:07

27:10

27:14

27:19

27:24

27:28

27:34

27:37

27:41

27:45

27:48

27:54

27:57

27:59

28:00

28:03

28:13

28:19

28:25

28:30

28:35

28:49

29:01

29:04

29:07

29:08

29:12

29:17

29:21

29:26

29:27

29:29

29:29

29:32

29:39

29:41

29:45

29:54

29:58

30:00

30:03

30:06

30:09

30:13

30:15

30:18

30:20

30:25

30:29

30:34

30:39

30:42

30:47

30:53

30:58

31:01

31:05

31:11

31:18

31:21

31:24

31:25

31:31

31:36

31:41

31:48

31:54

32:00

32:05

32:12

32:17

32:22

32:29

32:36

32:41

32:44

32:49

32:56

33:00

33:05

33:09

33:14

33:17

33:22

33:26

33:29

33:34

33:39

33:44

33:46

33:51

33:54

33:58

34:01

34:05

34:08

34:11

34:13

34:19

34:22

34:24

34:28

34:32

34:35

34:39

34:42

34:43

34:45

34:53

34:56

35:01

35:09

35:14

35:15

35:21

35:22

35:27

35:34

35:40

35:45

35:50

35:51

35:51

35:56

35:58

35:59

36:04

36:09

36:13

36:17

36:20

36:24

36:27

36:27

36:28

36:29

36:30

36:35

36:36

36:45

36:48

36:50

36:58

37:07

37:10

37:15

37:20

37:21

37:27

37:28

37:32

37:34

37:35

37:38

37:41

37:44

37:48

37:51

37:57

37:57

37:59

38:01

38:02

38:03

38:04

38:10

38:14

38:18

38:24

38:30

38:34

38:38

38:41

38:44

38:49

38:53

38:56

39:00

39:04

39:09

39:11

39:17

39:18

39:20

39:24

39:29

39:30

39:31

39:34

39:39

39:40

39:42

39:42

39:43

39:48

39:50

39:55

39:58

40:02

40:07

40:12

40:16

40:18

40:22

40:25

40:27

40:34

40:39

40:43

40:48

40:53

40:57

41:02

41:07

41:12

41:18

41:23

41:27

41:31

41:38

41:38

41:41

41:44

41:48

41:49

41:54

42:02

42:08

42:13

42:16

42:20

42:24

42:28

42:35

42:42

42:44

42:48

42:53

42:56

43:05

43:11

43:15

43:16

43:18

43:19

43:20

43:21

43:23

43:27

43:34

43:39

43:43

43:47

43:51

43:56

43:59

44:03

44:05

44:06

44:10

44:12

44:15

44:16

44:20

44:23

44:26

44:30

44:32

44:33

44:35

44:38

44:41

44:41

44:47

44:49

44:54

44:57

45:01

45:07

45:09

45:13

45:18

45:21

45:24

45:31

45:34

45:39

45:43

45:46

45:51

45:53

45:57

46:01

46:03

46:05

46:15

46:23

46:30

46:41

46:47

46:56

47:02

47:10

47:15

47:22

47:27

47:32

47:37

47:42

47:44

47:48

47:52

47:57

48:04

48:05

48:14

48:18

48:19

48:25

48:29

48:32

48:36

48:41

48:44

48:45

48:50

48:55

48:59

49:02

49:02

49:04

49:07

49:09

49:15

49:17

49:22

49:25

49:30

49:33

49:36

49:41

49:42

49:46

49:47

49:47

49:48

49:48

49:49

49:52

49:53

49:58

50:02

50:05

50:09

50:15

50:21

50:24

50:25

50:29

50:34

50:38

50:42

50:46

50:51

50:53

50:58

51:02

51:07

51:12

51:16

51:18

51:22

51:24

51:25

51:28

51:31

51:37

51:39

51:41

51:43

51:43

51:45

51:48

51:52

51:57

52:03

52:09

52:11

52:14

52:18

52:21

52:26

52:31

52:32

52:37

52:39

52:42

52:43

52:45

52:48

52:49

52:51

52:52

52:53

53:00

53:02

53:09

53:15

53:21

53:27

53:31

53:36

53:37

53:38

53:39

53:40

53:50

54:01

54:07

54:12

54:17

54:23

54:27

54:31

54:32

54:33

54:35

54:42

54:42

54:43

54:45

54:46

54:47

54:50

54:54

54:56

55:02

55:05

55:10

55:13

55:17

55:18

55:24

55:29

55:34

55:39

55:42

55:48

55:53

55:58

56:03

56:07

56:12

56:18

56:23

56:26

56:27

56:31

56:35

56:39

56:42

56:46

56:50

56:53

57:00

57:05

57:10

57:16

57:20

57:27

57:29

57:31

57:33

57:34

57:35

57:38

57:39

57:40

57:48

57:51

57:53

57:59

58:00

58:04

58:06

58:11

58:13

58:16

58:23

58:27

58:33

58:37

58:42

58:48

58:54

59:00

59:04

59:10

59:15

59:19

59:25

59:29

59:32

59:37

59:42

59:51

59:52

59:53

01:00:03

01:00:09

01:00:12

01:00:13

01:00:18

01:00:22

01:00:26

01:00:31

01:00:32

01:00:36

01:00:39

01:00:43

01:00:49

01:00:51

01:00:56

01:00:59

01:01:04

01:01:05

01:01:10

01:01:12

01:01:12

01:01:17

01:01:17

01:01:20

01:01:22

01:01:24

01:01:25

01:01:30

01:01:35

01:01:44

01:01:52

01:01:57

01:02:04

01:02:10

01:02:15

01:02:20

01:02:22

01:02:25

01:02:29

01:02:32

01:02:37

01:02:41

01:02:46

01:02:51

01:02:56

01:03:00

01:03:03

01:03:04

01:03:05

01:03:11

01:03:12

01:03:13

01:03:16

01:03:20

01:03:26

01:03:30

01:03:31

01:03:36

01:03:39

01:03:39

01:03:41

01:03:46

01:03:49

01:03:53

01:03:58

01:04:00

01:04:02

01:04:09

01:04:11

01:04:16

01:04:21

01:04:29

01:04:35

01:04:39

01:04:43

01:04:48

01:04:52

01:04:56

01:04:58

01:05:02

01:05:06

01:05:10

01:05:11

01:05:12

01:05:19

01:05:22

01:05:32

01:05:34

01:05:38

01:05:43

01:05:46

01:05:50

01:05:54

01:05:56

01:05:59

01:06:01

01:06:04

01:06:05

01:06:08

01:06:14

01:06:15

01:06:16

01:06:18

01:06:19

01:06:20

01:06:22

01:06:26

01:06:31

01:06:46

01:06:51

01:07:01

01:07:12

01:07:26

01:07:27

01:07:28

01:07:33

01:07:40

01:07:41

01:08:07

01:08:23

01:08:24

01:08:25

01:08:26

01:08:26

01:08:27

01:08:27

01:08:28

01:08:30

01:08:31

01:08:33

01:08:33

01:08:35

01:08:35

01:08:36

01:08:42

01:08:45

01:08:50

01:08:54

01:08:56

01:08:57

01:08:57

01:08:59

01:09:00

01:09:02

01:09:03

01:09:05

01:09:05

01:09:07

01:09:08

01:09:10

01:09:12

01:09:14

01:09:16

01:09:17

01:09:17

01:09:19

01:09:22

01:09:23

01:09:24

01:09:26

01:09:30

01:09:34

01:09:41

01:09:47

01:09:54

01:10:00

01:10:06

01:10:13

01:10:18

01:10:24

01:10:31

01:10:35

01:11:02